Data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates breast cancer to be the most commonly diagnosed cancer this year, with 19,974 cases of breast cancer predicted to be diagnosed across Australia. It also found that 1,532 cases of ovarian cancer will be diagnosed by the end of 2020. A piece of research headed by Queen Mary University of London has looked at broadening screening to help prevent these cancers.

This latest research paper looked at testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 – genes associated with increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Although not the only genetic abnormalities that are associated with increased risk, BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most recognised breast and ovarian cancer-causing genes.

These gene mutations cause around 10-20 per cent of ovarian and 6 per cent of breast cancers. If mutation carriers could be identified before they develop disease, most of these cancers could be prevented by drugs, increased screening or surgery.

WATCH: Channel 10 news story on BRCA testing research with genetic pathologist, Dr Melody Caramins

The research suggests that screening more widely for breast and ovarian cancer gene mutations could prevent millions more breast and ovarian cancer cases across the world compared to current clinical practice. The research also shows that it is cost effective in high and upper-middle income countries. This means if guidelines were changed to offer screening to more women this could be beneficial to patients and the health system in the Australian economic landscape.

Genetic testing in Australia

As with all pathology tests, genetic testing is provided within a medical framework to ensure that testing is offered where it is clinically appropriate, offers benefit to the patient and is completed under strict quality guidelines. All predictive genetic testing must be done in the context of pre-test genetic counselling by highly qualified specialists as there are complex consequences for the patient and for their family that must be discussed prior to testing. This allows people to make an informed decision about whether to have the test.

Currently in Australia the guidelines to refer someone for testing are quite strict and rely on specific family history of cancer. This research makes the case to potentially reconsider those clinical guidelines for this type of testing, and whether the current threshold is appropriate and the most beneficial for Australian patients and the health system.

Nicole Braude is an ambassador for Pink Hope, an Australian organisation that provides women the necessary tools to assess, manage and reduce their risk of breast and ovarian cancer, while providing personalised support for at risk women. Nicole’s grandma died from breast cancer when she was only 34 years old. Getting the appropriate testing was something that was always in the back of Nicole’s mind growing up.

Speaking about her and her family’s experience of genetic testing and breast cancer Nicole said: “It turns out genetic testing was the best thing we ever did as it saved my sister’s life. They found the gene and she had a double mastectomy. I decided to have preventative surgery too after I took a risk assessment which revealed I had an 89.7% chance of developing breast cancer before the age of 40.I had the surgery and never looked back, I’m now 25 weeks pregnant and my baby is BRCA free. That news came as such a relief because my child will never have to worry like I did.”

Let’s talk numbers

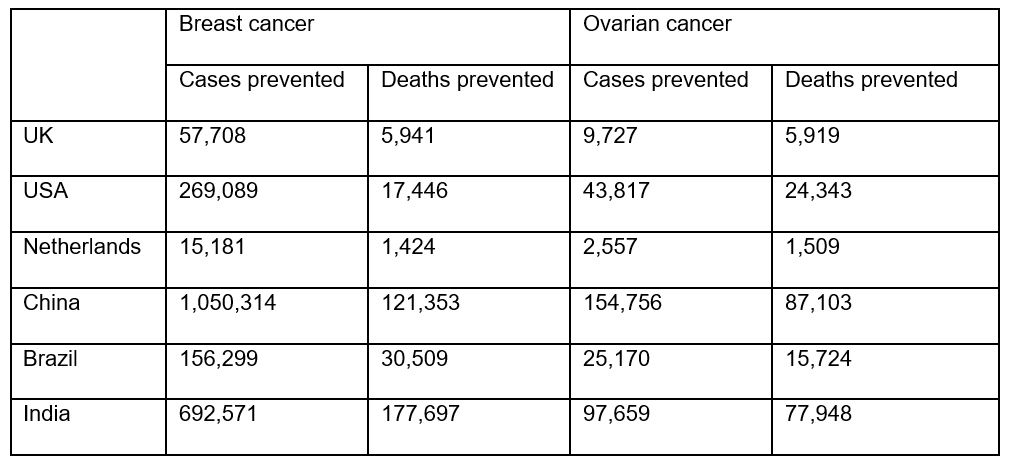

Findings by Queen Mary University of London suggest that population based BRCA testing can prevent an additional 2,319-2,666 breast cancer and 327-449 ovarian cancer cases per million women than the current clinical strategy. The table below explains how that would be translated in terms of preventable deaths in each of the countries examined in this particular study.

Dr Melody Caramins is the National Director of Genomics and former chair of the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia’s Genetics Advisory Committee. Speaking about the research findings Dr. Caramins said:

“The research results are startling and confirms that we must invest in cancer prevention. By broadening a simple genetic test and offering it to a wider population we could save thousands of Australian lives. Identifying a mutation at an early stage is the key and now we know that it can be cost effective within the healthcare system. The research findings are truly amazing.”

BRCA screening tests are available in Australia but only those who fit certain criteria, such as a strong family history of breast cancer, will be referred for testing. Broader population screening is not currently available.

Any changes to clinical guidelines for BRCA screening tests would require careful consideration and ensuring the appropriate resources were in place to support individuals and families. Genetic counselling is an important part of the process and must be available to anyone being offered testing. This is a highly skilled and complex role that requires years of training.

There are online resources available such as Pink Hope’s Know Your Risk tool, which was developed in partnership with Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre. Anyone who is concerned about their risk of breast or ovarian cancer can also speak to their GP in the first instance who may then refer them to a Family Cancer Centre, Clinical Geneticist, or Genetic Oncologist.

This research was led by Prof Ranjit Manchanda (Queen Mary University of London) and supported by Dr Rosa Legood (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine). This research was an international collaboration involving research teams from Queen Mary University of London, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and involved Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (Netherlands); Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo (Brazil); Peking University, Beijing (China); Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur (India); Presidency University, Kolkata (India); Tata Medical Centre, Kolkata (India); University of Melbourne, Victoria (Australia); Newcastle University (UK).