What is malaria?

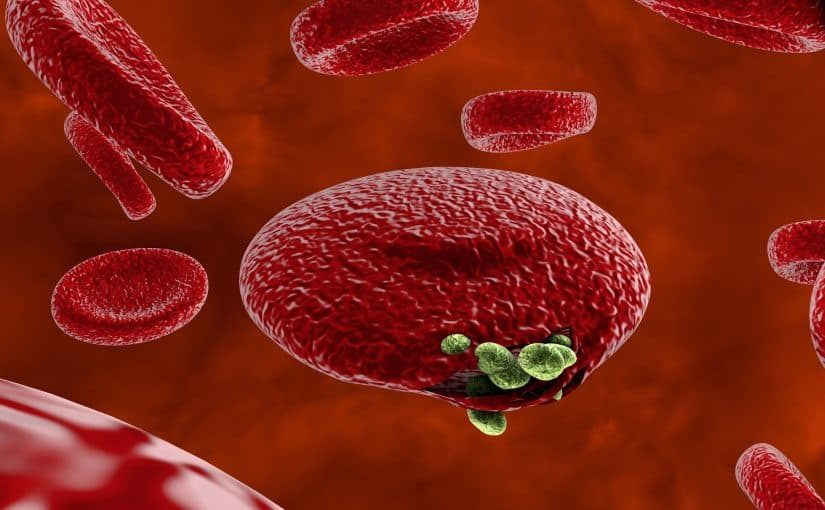

Malaria is an infectious disease spread by plasmodium parasites that enter the bloodstream, usually as the result of a mosquito bite, although very rarely it may be contracted through congenital infection, the sharing of needles or a blood transfusion.

Once in the blood stream the parasites travel to the liver where they incubate and lay dormant, most commonly for a period of 7-30 days but this may stretch out to months or even years if an insufficient dosage of anti-malarial medication was taken. Thereafter they leave the liver and enter the bloodstream.

Where is malaria common?

While the World Health Organisation declared Australia malaria-free in 1981, that doesn’t make Australians immune to it. Most commonly malaria cases in Australia are contracted in Papua New Guinea and Asia.

Malaria is a common problem in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as regions of South and Central America, the Caribbean, Eastern Europe and the South Pacific. So for travelling Australians it’s important to make sure you check with your doctor, on advice re active and passive prophylaxis and resources like smartraveller.org.au for notices on infectious diseases.

Symptoms

Often, but not always, symptoms present as flu-like (fevers, chills, aches, sweats, headaches and general unwellness). Some sufferers may experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, anaemia and jaundice. Often this will occur 14 days or so after exposure but may occur as early as 7 days or several months.

Symptoms may go in cycles, getting better and worse every 2-3 days. An enlarged spleen or liver may also be a symptom. Severe cases of malaria can impact the brain, kidneys and lungs; causing seizures, respiratory distress, coma, organ failure and death.

Testing

Given the wide range of symptoms, its slow materialisation and its tendency to change over time, there is no definitive lupus test as such. Instead a medical diagnosis is usually made on the basis of signs and symptoms in combination with tests. These tests include:

Thick and thin blood films preferably three blood samples are taken within a 12-24 hour time period to help diagnose the condition. The ‘thick’ films are used to determine quantities of the parasite, with a large number of blood cells inspected under a microscope. The ‘thin’ films are used to identify the type of plasmodium parasite causing the infection, which is important in determining treatment (see below).

Rapid diagnostic tests this is a ‘dipstick’ test used when microscopes aren’t available. A blood sample is taken and applied to a strip which changes colour. Most commonly used in remote areas, these quick tests allow for early diagnosis and treatment, although there are usually follow up microscopy tests to confirm a diagnosis.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) where microscopy is not available in a lab, this test amplifies DNA to allow for detection and identification of a malarial parasite. It is particularly useful when there is mixed infection and low parasite loads.

Treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment is important and a medical assessment should be made as soon as possible. The course of treatment prescribed will be determined by the species of plasmodium that has caused the infection, the area the disease was acquired in, and the state of health of the patient. Special attention is required for pregnant women and children.

For straightforward cases of malaria, treatment may be oral, while more complex forms of malaria may require intravenous medication.

Some type of malarial infection, such as P. vivax and P. ovale, can relapse and stay dormant in the liver, requiring further treatment.

The condition is monitored by blood films that test for the parasite count. Pathologists are looking for a drop off in the parasite count to determine if a treatment appears to be working.