Australians with a family history of breast and ovarian cancer will soon be more readily able to undergo genetic tests to assess their risk of developing the diseases.

Up until now, patients have had to pay between $600 and $2,000 to receive BRCA1 and 2 genetic tests. From November 1st, the tests will become more readily available to Australians as they are now subsidised under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for eligible patients in consultation with their doctor.

Both high-risk patients and their families will be able to access the free test once medical specialists assess their family history and risk.

Dr Melody Caramins, an ambassador for Pathology Awareness Australia and expert in genetics, was thrilled to hear of the upcoming addition to the MBS:

“It is a huge milestone and will significantly improve the lives of Australians, offering more choice via access to affordable screening and treatment options,” Dr Caramins said.

“If an individual is a carrier of a BRCA mutation, they will have additional treatments available to them. This is certainly the case if they already have breast cancer, however if they don’t have breast cancer, they will have access to monitoring and the possibility to take preventative measures such as a mastectomy.”

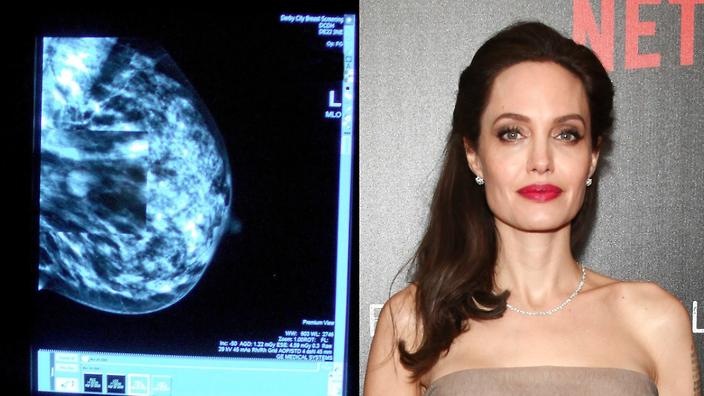

In 2013, the public became more aware of the BRCA gene tests when US actress Angelina Jolie spoke publicly about her decision to undergo a double mastectomy after genetic testing revealed she had an 87 per cent chance of developing breast cancer.

Today, breast cancer is the most common cancer among Australian women, with an estimated 17,586 new cases expected to be diagnosed this year. It’s estimated that 3000 men and women could die from the disease in 2017.

A recent study by researchers from the Peter Mac Cancer Centre, University of Melbourne and Cancer Council Victoria found that women with BRCA1 mutations have on average a 72% risk of developing breast cancer by the time they turn 80. Those with the BRCA2 mutation had a 69 per cent chance.

Ovarian Cancer Australia also estimates that women who inherit a faulty BRCA1 gene have approximately a 40% risk of developing the disease, while those who inherit the BRCA2 gene face a 10-15% risk.

Increased access to the test means more patients with the mutation are likely to be identified, enabling them to take preventative measures against breast or ovarian cancer.

For the patients’ relatives, the impact is just as significant. When a mutation is found, family members can have testing to assess their own risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer – and of passing the same mutation on to their children. Female relatives with a mutation can take specific precautions to reduce the chance of a serious cancer diagnosis.

“This is a crucial step in mainstreaming genetic testing, so families don’t have to have to live in doubt any longer”,’ said Dr Caramins.